The Sloan Digital Sky Survey’s fifth generation – a groundbreaking project to bolster our understanding of the formation and evolution of galaxies, including the Milky Way – collected its very first observations on the evening of October 23.

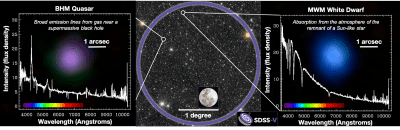

Image: The Sloan Digital Sky Survey’s fifth generation made its first observations earlier this month. This image shows a sampling of data from those first SDSS-V data. The central sky image is a single field of SDSS-V observations. The purple circle indicates the telescope’s field-of-view on the sky, with the full Moon shown as a size comparison. SDSS-V simultaneously observes 500 targets at a time within a circle of this size. The left panel shows the optical-light spectrum of a quasar–a supermassive black hole at the center of a distant galaxy, which is surrounded by a disk of hot, glowing gas. The purple blob is an SDSS image of the light from this disk, which in this dataset spans about 1 arcsecond on the sky, or the width of a human hair as seen from about 21 meters (63 feet) away. The right panel shows the image and spectrum of a white dwarf — the left-behind core of a low-mass star (like the Sun) after the end of its life.Image Credit: Hector Ibarra Medel, Jon Trump, Yue Shen, Gail Zasowski, and the SDSS-V Collaboration. Central background image: unWISE / NASA/JPL-Caltech / D.Lang (Perimeter Institute).

“In a year when humanity has been challenged across the globe, I am so proud of the worldwide SDSS team for demonstrating — every day — the very best of human creativity, ingenuity, improvisation, and resilience. It has been a wild ride, but I’m happy to say that the pandemic may have slowed us, but it has not stopped us,” says Juna Kollmeier, director of the project known as SDSS-V.

The project is funded primarily by an international consortium of member institutions, along with grants from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, U.S. National Science Foundation, and the Heising-Simons Foundation.

Jonathan Trump, UConn assistant professor of physics, has a long history with SDSS, and is one of the architects for the fifth installment of the program. He is also serving as the cadence coordinator for the project’s black hole science goals.

“My very first undergrad research project was an SDSS project. I have worked on SDSS as a post-doc, and I am working on it now as faculty,” Trump says. “I’ve been part of it from the first SDSS iteration, and as it has taken off, so has my career.”

Trump and his colleagues will focus on three primary areas of investigation with SDSS-V, each exploring different aspects of the cosmos using different spectroscopic tools. Together, these three project pillars—called “Mappers”—will observe more than six million objects in the sky, and monitor changes in more than a million of those objects over time.

The survey’s Local Volume Mapper will enhance our understanding of galaxy formation and evolution by probing the interactions between the stars that make up galaxies and the interstellar gas and dust that is dispersed between them. The Milky Way Mapper will reveal the physics of stars in our Milky Way, the diverse architectures of its star and planetary systems, and the chemical enrichment of our galaxy since the early universe. The Black Hole Mapper will measure masses and growth over cosmic time of the supermassive black holes that reside in the hearts of galaxies, as well as the smaller black holes left behind when stars die.

Trump says another novel aspect of SDSS-V is repeat observation, which he will be scheduling over the duration of the project as cadence coordinator, to help gather more data about the evolution of different features of matter near black holes.

“SDSS-V has more repeat observations as part of the plan. I would say that broadly in astronomy there is an emphasis on repeat observations,” he says. “For instance, black holes are fascinating – they are rips in space-time, and they are extremely exotic. Even one snapshot reveals how exotic they are, but they are also dramatically variable, and when we observe them day-to-day, week-to-week, year-to-year, we see dramatic changes in their emission, which we think correspond to dramatic changes just beyond the event horizon of the black hole. We are learning that you can reveal a lot about the physics of what is going on around black holes by watching them as a function of time.”

SDSS-V will operate out of both Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, home of the survey’s original 2.5-meter telescope, and Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, where it uses the 2.5-meter du Pont telescope. SDSS-V’s first observations were gathered in New Mexico with existing SDSS instruments, as a necessary change of plans due to the pandemic. As laboratories and workshops around the world navigate safe reopening, SDSS-V’s own suite of new innovative hardware is on the horizon—in particular, systems of automated robots to aim the fiber optic cables used to collect the light from the night sky. These will be installed at both observatories over the next year. New spectrographs and telescopes are also being constructed to enable the Local Volume Mapper observations.

Trump points out that another important aspect of SDSS, especially in a time of remote learning and researching, is the fact that data are made public and accessible.

“It is easy to access and mine the SDSS databases and make interesting studies,” he says. “They have wonderful tutorials for schools and for researchers to get started. They make it so easy for people to dive in. It is a very rich opportunity; it’s well organized and publicly shared.”

To learn more about the program, explore the data, or keep up with the research, visit https://www.sdss5.org/

This article first appeared online on UConn Today, November 2, 2020.