Physicists used to think that superconductivity – electricity flowing without resistance or loss – was an all or nothing phenomenon. But new evidence suggests that, at least in copper oxide superconductors, it’s not so clear cut.

Superconductors have amazing properties, and in principle could be used to build loss-free transmission lines and magnetic trains that levitate above superconducting tracks. But most superconductors only work at temperatures close to absolute zero. This temperature, called the critical temperature, is often only a few degrees Kelvin and requires liquid helium to stay that cold, making such superconductors too expensive for most commercial uses. A few superconductors, however, have a much warmer critical temperature, closer to the temperature of liquid nitrogen (77K), which is much more affordable.

Many of these higher-temperature superconductors are based on a two-dimensional form of copper oxide.

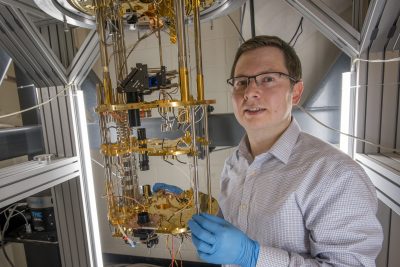

“If we understood why copper oxide is a superconductor at such high temperatures, we might be able to synthesize a better one” that works closer to room temperature (293K), says UConn physicist Ilya Sochnikov.

Sochnikov and his colleagues at Rice University, Brookhaven National Lab and Yale recently figured out part of that puzzle, and they report their results in the latest issue of Nature.

Their discovery was about how electrons behave in copper oxide superconductors. Electrons are the particles that carry electric charge through our everyday electronics. When a bunch of electrons flow in the same direction, we call that an electric current. In a normal electric circuit, say the wiring in your house, electrons bump and jostle each other and the surrounding atoms as they flow. That wastes some energy, which leaves the circuit as heat. Over long distances, that wasted energy can really add up: long-distance transmission lines in the U.S. lose on average 5% of their electricity before reaching a consumer, according to the Energy Information Administration.

But in a superconductor below its critical temperature, electrons behave totally differently. Instead of bumping and jostling, they pair up and move in sync with the other electrons in a kind of wave. If electrons in a normal current are a rushing, uncoordinated mob, electrons in a superconductor are like dancing couples, gliding across the floor like people in a ballroom. It’s this friction-free dance – coherent motion – of paired electrons that makes a superconductor what it is.

The electrons are so happy in pairs in a superconductor that it takes a certain amount of energy to pull them apart. Physicists can measure this energy with an experiment that measures how big a voltage is needed to tear an electron away from its partner. They call it the ‘gap energy’. The gap energy disappears when the temperature rises above the critical temperature and the superconductor changes into an ordinary material. Physicists assumed this is because the electron pairs have broken up. And in classic, low-temperature superconductors, it’s pretty clear that that’s what’s happening.

But Sochnikov and his colleagues wanted to know whether this was really true for copper oxides. Copper oxides behave a little differently than classic superconductors. Even when the temperature rises well above the critical level, the energy gap persists for a while, diminishing gradually. It could be a clue as to what makes them different.

The researchers set up a version of the gap energy experiment to test this. They made a precise sandwich of two slices of copper oxide superconductor separated by a thin filling of electrical insulator. Each slice was just a few nanometers thick. The researchers then applied a voltage between them. Electrons began to tunnel from one slice of copper oxide to the other, creating a current.

By measuring the noise in that current, the researchers found that a significant number of the electrons seemed to be tunneling in pairs instead of singly, even above the critical temperature. Only about half the electrons tunneled in pairs, and this number dropped as the temperature rose, but it tapered off only gradually.

“Somehow they survive,” Sochnikov says, “they don’t break fully.” He and his colleagues are still not sure whether the paired states are the origin of the high-temperature superconductivity, or whether it’s a competing state that the superconductor has to win out over as the temperature falls. But either way, their discovery puts a constraint on how high temperature superconductors happen.

“Our results have profound implications for basic condensed matter physics theory,” says co-author Ivan Bozovic, group leader of the Oxide Molecular Beam Epitaxy Group in the Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science Division at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory and professor of applied physics at Yale University. Sochnikov agrees.

“There’s a thousand theories about copper oxide superconductors. This work allows us to narrow it down to a much smaller pool. Essentially, our results say that any theory has to pass a qualifying exam of explaining the existence of the observed electron pairs,” Sochnikov says. He and his collaborators at UConn, Rice University, and Brookhaven National Laboratory plan to tackle the remaining open questions by designing even more precise materials and experiments.

The research work at UConn was funded by the State of Connecticut through laboratory startup funds.

This article first appeared on UConn Today, August 21, 2019.

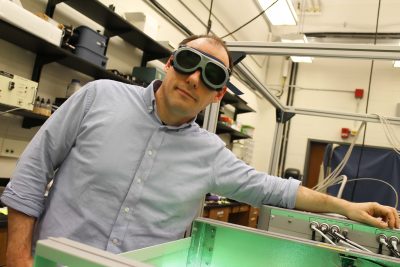

Daniel McCarron, assistant professor of physics, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, will receive $645,000 over five years for his work on the development of techniques to trap large groups of molecules and cool them to temperatures near absolute zero. The possible control of molecules at this low temperature provides access to new research applications, such as quantum computers that can leverage the laws of quantum mechanics to outperform classical computers.

Daniel McCarron, assistant professor of physics, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, will receive $645,000 over five years for his work on the development of techniques to trap large groups of molecules and cool them to temperatures near absolute zero. The possible control of molecules at this low temperature provides access to new research applications, such as quantum computers that can leverage the laws of quantum mechanics to outperform classical computers. August 19, 2019

August 19, 2019