UConn on the Front Line to Glimpse Farthest Reaches of Universe

Two UConn physics professors will be among the world’s first scientists to explore the universe using the new James Webb Space Telescope, as announced earlier this month by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

[The] James Webb [Space Telescope] will begin teaching us entirely new things … things we don’t even know about. — Jonathan Trump

Just like the highly anticipated release of a new phone, game, or gadget, astrophysicists worldwide are eager to start using the new telescope, the latest technology for viewing distant elements of our universe, which is currently set to launch in 2019. But rather than stand in line for hours outside a store, researchers had to submit compelling proposals to secure their spot in line and an opportunity to use the new technology.

The highly competitive, peer-reviewed James Webb Space Telescope Early Release Scienceprogram was created to test the capabilities of the new observatory and to showcase the tools the telescope is equipped with. Of more than 100 proposals submitted, only 13 were chosen to participate in the early release phase, including two separate proposals involving UConn researchers Kate Whitaker and Jonathan Trump, both assistant professors of physics.

Passing the Telescope Torch

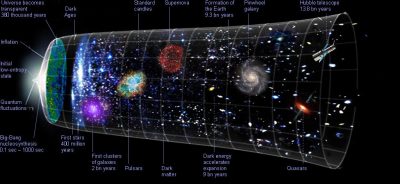

The James Webb Space Telescope, designed to be a large space-based observatory optimized for infrared wavelengths, will be the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope. The Hubble telescope has been a versatile workhorse and vital tool since its launch in 1990, allowing researchers to peer deep into space and get crisp glimpses of distant galaxies.

But it has technological limitations, and is not currently scheduled for any upgrades or servicing. Since its last service in 2009, Whitaker says, many researchers have been keeping their fingers crossed that it would continue functioning. Hubble is currently the only way to make observations that are required for the type of research she and many others conduct.

“A lot of my research right now is pushing Hubble to its limits,” she notes. “It’s an exciting time, because with the capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope, we will really push into the frontiers of research.”

The James Webb Space telescope is equipped with tools that will surpass Hubble’s capabilities. Webb will be launched further into space and will be capable of powerful imaging that will produce sharper images and be able to capture images into the infrared range.

Peering into the infrared range allows researchers to observe signatures, in the form of light, from events that happened long ago. The universe is constantly expanding and as light travels, it gets stretched over time, Whitaker explains. The further back you go, say a few billion years or so, the light is stretched so much that it will shift from the visible region of the spectrum into the infra-red.

Cutting-Edge Research, Winning Proposals

Whitaker is a science collaborator on a proposal titled “TEMPLATES: Targeting Extremely Magnified Panchromatic Lensed Arcs and Their Extended Star formation,” exploring star formation in galaxies at a distance of around 10 billion years in the past, something impossible to observe until the high resolution of the new telescope. They hope to more closely study characteristics of those distant galaxies that have until now, only been discernible in more local galaxies.

“Since we cannot travel to these distant galaxies, all we can do is sit here and wait for their light to reach our telescopes,” says Whitaker.

Trump is a co-investigator on the proposal called “CEERS: The Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey,” a plan to conduct an extragalactic survey in hopes of gaining insights into the formation of the first galaxies following the big bang. They plan to look at aspects of the assembly of galaxies, including their number density, chemical abundance, star formation, and the growth of supermassive black holes.

“Hubble has totally transformed our view of the universe and James Webb will begin teaching us entirely new things,” Trump says. “I’m incredibly excited to think about all of the things we don’t even know about, that James Webb will begin to tell us.”

The Early Release Program is aimed not only to showcase the capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope right away, but to make the data publicly available as soon as possible. It is anticipated that the data will facilitate huge breakthroughs in research.

Stay tuned: 2019 promises to be an exciting year in astrophysics.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control lists

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control lists  As a research assistant in the physics department at UCONN, I assisted in the alignment, maintenance, and principles of operation of the various apparatuses and measurement techniques used within cold atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) experimental physics research. This included optical components, laser alignment, laser locking, saturation absorption spectroscopy, and electrodynamic ion trapping. Some specific experiments ran included measuring the fraction of a trapped, sodium atom-cloud (fe) pumped into an optically excited state using laser beams as well as measuring the temperature of a trapped, neutral atom-cloud via spatio-temporal fluorescence imaging.

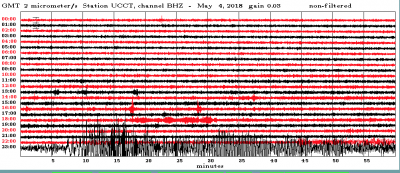

As a research assistant in the physics department at UCONN, I assisted in the alignment, maintenance, and principles of operation of the various apparatuses and measurement techniques used within cold atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) experimental physics research. This included optical components, laser alignment, laser locking, saturation absorption spectroscopy, and electrodynamic ion trapping. Some specific experiments ran included measuring the fraction of a trapped, sodium atom-cloud (fe) pumped into an optically excited state using laser beams as well as measuring the temperature of a trapped, neutral atom-cloud via spatio-temporal fluorescence imaging. Attached is our record for the Mw 6.9 earthquake associated with eruptions of the Kilauea volcano on the big island of Hawaii. The large waves arriving after 2300 GMT are surface waves (elastic energy that exponentially decays with depth away from the surface) traveling from the earthquake to us. The beating pattern is characteristic of surface waves interfering from slightly different multi paths as they are refracted by the sharp transition in elastic structure between the ocean and continent.

Attached is our record for the Mw 6.9 earthquake associated with eruptions of the Kilauea volcano on the big island of Hawaii. The large waves arriving after 2300 GMT are surface waves (elastic energy that exponentially decays with depth away from the surface) traveling from the earthquake to us. The beating pattern is characteristic of surface waves interfering from slightly different multi paths as they are refracted by the sharp transition in elastic structure between the ocean and continent.

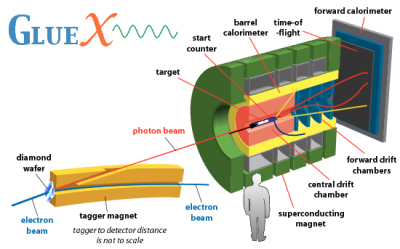

Scientists are one step closer to understanding the strong force that binds quarks together forever. Researchers working with the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (J-Lab) have published their first scientific results since the accelerator energy was increased from six billion electron volts (GeV) to 12 GeV. The upgrade was commissioned to enable the next generation of physics experiments that will allow scientists to see smaller bits of matter than have ever been seen before. The first publication from the upgraded CEBAF was published by the Gluonic Excitation Project (GlueX) in the April issue of Physical Review C, available

Scientists are one step closer to understanding the strong force that binds quarks together forever. Researchers working with the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (J-Lab) have published their first scientific results since the accelerator energy was increased from six billion electron volts (GeV) to 12 GeV. The upgrade was commissioned to enable the next generation of physics experiments that will allow scientists to see smaller bits of matter than have ever been seen before. The first publication from the upgraded CEBAF was published by the Gluonic Excitation Project (GlueX) in the April issue of Physical Review C, available