– Donna Weaver & Ray Villard, Space Telescope Science Institute

The University of Connecticut’s Katherine Whitaker is part of a team of astronomers who have put together the largest and most comprehensive “history book” of the universe from 16 years’ worth of observations from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope.

The deep-sky mosaic provides a wide portrait of the distant universe, containing 200,000 galaxies that stretch back through 13.3 billion years of time to just 500 million years after the Big Bang. The tiny, faint, most distant galaxies in the image are similar to the seedling villages from which today’s great galaxy star-cities grew. The faintest and farthest galaxies are just one ten billionth the brightness of what the human eye can see.

The image yields a huge catalog of distant galaxies. “Such exquisite high-resolution measurements of the legacy field catalog of galaxies enable a wide swath of extragalactic study,” says Whitaker, the catalog lead researcher. “Often, these kinds of surveys have yielded unanticipated discoveries that have had the greatest impact on our understanding of galaxy evolution.”

The ambitious endeavor, called the Hubble Legacy Field, also combines observations taken by several Hubble deep-field surveys, including the eXtreme Deep Field (XDF), the deepest view of the universe. The wavelength range stretches from ultraviolet to near-infrared light, capturing all the features of galaxy ‘assembly over time.

“Now that we have gone wider than in previous surveys, we are harvesting many more distant galaxies in the largest such dataset ever produced,” says Garth Illingworth of the University of California, Santa Cruz, and leader of the team. “This one image contains the full history of the growth of galaxies in the universe, from their times as infants to when they grew into fully-fledged ‘adults.’”

Illingworth says he anticipates that the survey will lead to an even more coherent and in-depth understanding of the universe’s evolution in the coming years.

The deep-sky mosaic provides a wide portrait of the distant universe, containing 200,000 galaxies that stretch back through 13.3 billion years of time to just 500 million years after the Big Bang.

Galaxies trace the expansion of the universe, offering clues to the underlying physics of the cosmos, showing when the chemical elements originated and enabled the conditions that eventually led to the appearance of our solar system and life.

This new wider view contains 100 times as many galaxies as in the previous deep fields. The new portrait, a mosaic of multiple snapshots, covers almost the width of the full Moon, and chronicles the universe’s evolutionary history in one sweeping view. The portrait shows how galaxies change over time, building themselves up to become the giant galaxies seen in the nearby universe. The broad wavelength range covered in the legacy image also shows how galaxy stellar populations look different depending on the color of light.

The legacy field also uncovers a zoo of unusual objects. Many of them are the remnants of galactic “train wrecks,” a time in the early universe when small, young galaxies collided and merged with other galaxies.

Assembling all of the observations was an immense task. The image comprises the collective work of 31 Hubble programs by different teams of astronomers. Hubble has spent more time on this tiny area than on any other region of the sky, totaling more than 250 days.

The image, along with the individual exposures that make up the new view, is available to the worldwide astronomical community through the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST), an online database of astronomical data from Hubble and other NASA missions.

The new set of Hubble images, created from nearly 7,500 individual exposures, is the first in a series of Hubble Legacy Field images. The team is working on a second set of images, totaling more than 5,200 Hubble exposures, in another area of the sky.

In addition, NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will allow astronomers to push much deeper into the legacy field to reveal how the infant galaxies actually grew. Webb’s infrared coverage will go beyond the limits of Hubble and Spitzer to help astronomers identify the first galaxies in the universe.

The Hubble Legacy Fields program, supported through AR-13252 and AR-15027, is based on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, obtained at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-26555.

This article first appeared in UConn Today on May 2, 2019.

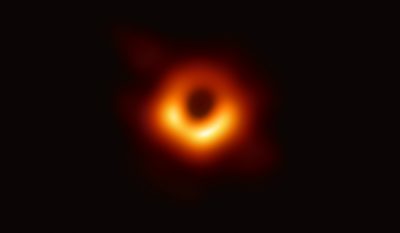

Physics major Brenna Robertson has been selected as the recipient of the 2018 Mark Miller Undergraduate Research Award. Brenna’s proposal, which focuses on modeling supermassive black hole spin using spectral emission diagrams, was selected from among a strong pool of applicants. Brenna Robertson is working with Prof. Jonathan Trump.

Physics major Brenna Robertson has been selected as the recipient of the 2018 Mark Miller Undergraduate Research Award. Brenna’s proposal, which focuses on modeling supermassive black hole spin using spectral emission diagrams, was selected from among a strong pool of applicants. Brenna Robertson is working with Prof. Jonathan Trump.

Gizmodo has recently launched a new series of articles to explore how the best images in science were created and why. In

Gizmodo has recently launched a new series of articles to explore how the best images in science were created and why. In