Scientists are one step closer to understanding the strong force that binds quarks together forever. Researchers working with the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (J-Lab) have published their first scientific results since the accelerator energy was increased from six billion electron volts (GeV) to 12 GeV. The upgrade was commissioned to enable the next generation of physics experiments that will allow scientists to see smaller bits of matter than have ever been seen before. The first publication from the upgraded CEBAF was published by the Gluonic Excitation Project (GlueX) in the April issue of Physical Review C, available online through the APS web site.

Scientists are one step closer to understanding the strong force that binds quarks together forever. Researchers working with the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (J-Lab) have published their first scientific results since the accelerator energy was increased from six billion electron volts (GeV) to 12 GeV. The upgrade was commissioned to enable the next generation of physics experiments that will allow scientists to see smaller bits of matter than have ever been seen before. The first publication from the upgraded CEBAF was published by the Gluonic Excitation Project (GlueX) in the April issue of Physical Review C, available online through the APS web site.

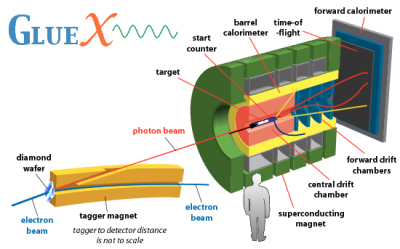

University of Connecticut Associate Professor of Physics Richard Jones and students have played a leading role in the GlueX experiment since its inception in a series of scientific workshops nearly 20 years ago. The goal of GlueX is to discover whether or not a new class of subatomic particle known as “hybrid mesons” actually exists, and if they do, to measure their masses and other properties. While their existence is widely accepted on the basis of general theoretical arguments, definitive experimental evidence is still lacking. If they exist, hybrid mesons should be much more massive than ordinary mesons, so they should decay into ordinary mesons before they can travel any further than a few femtometers from where they were formed. Hence, the GlueX experiment is equipped with a multi-particle tracking spectrometer with nearly full angular coverage and sensitivity to both charged particles and neutrals.

In this new paper, the GlueX team describes how they produced two ordinary mesons, the neutral pion and eta. While creating these two particles is fairly simple for an accelerator of the CEBAF’s magnitude, what was interesting to the researchers is that they were able to show that the linear polarization of the accelerator’s photon beam can provide enough information about how the meson was formed. They can use that information to narrow down theories about how the mesons were produced. The research team plans to continue to analyze the data the accelerator has produced since it was commissioned a year ago, and they will begin to collect new data this fall.

-based on a news article by Jocelyn Duffy